Mr. Williams' Strange Fruit

On first reading, I don't even know what to say about this bit of decayed tripe, but I know I've got to say something.

On first reading, I don't even know what to say about this bit of decayed tripe, but I know I've got to say something.Let's start with ol' Walt's depiction of himself as part of the generation that whupped the Nazis in WWII ("my generation"): "Today's Americans are vastly different from those of my generation who fought the life-and-death struggle of World War II."

Now, why does ol' Walt begin in this fashion? Why does Walt begin a screed on nuking the Middle East with an association of himself with WWII? According to his bio, Williams was no more than nine years old at the end of WWII. He was no more a direct functionary in that conflict than Howdy Doody. Maybe he can take credit for pitching in a dented pot toward a scrap metal drive, but that's about the extent of his contribution in that war. His generation? No. His parent's generation did that heavy lifting, not his.

But, he wants you, his reader, to think that his personal experience in that war was somehow sufficiently adult and mature in nature to inform his judgment now about the current situation in the Middle East. It's a rhetorical sleight-of-hand trick to convince the reader that his conflation of WWII and current events is based on his intimate and personal knowledge of war in that historical context--about which, as a nine-year-old, he could have known nothing in the way of actual personal combat.

Throughout, Williams avoids two salient points which would induce sensible people to differentiate current conditions from WWII. The first, of course, is that our participation in WWII was initiated by the actions of two nation states--Japan and Germany. We declared war on Japan shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Germany declared war on us on Dec. 8th, 1941. Notable difference there with regard to world war declared by nation states on one another and terrorism as it is currently expressed in the world. The second point to be made is that the experience of WWII has informed the world of the horrors of precisely the sorts of conflagrations which Williams suggests are not employed today because of "handwringing" and "appeasement." If there are attempts to avoid them today, it is exactly because of that dark knowledge.

And, yes, let's just bring color into this for a moment, because it bears on Williams' conclusions. In that war which Williams thinks defined American principles, U.S. troops were largely segregated when stateside. Japanese-American volunteers (those that weren't confined in internment camps--I guess one of the values we were fighting for in WWII was, therefore, xenophobia) were shunted into units such as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, while black folks, like Williams' kin, were only allowed to fly in segregated units such as the Tuskegee Airmen. The services weren't desegregated until Truman's order after the war. And Truman was a Democrat, not one of Williams' current racist brethren in the right wing. If Williams' current friends had been in charge of the government from then to now, he'd still be drinking from "Colored Only" water fountains and getting the shit beat out of him if he didn't look down when a white man's wife passed him on the sidewalk.

Williams' political allies are racists, closeted and otherwise. And he thinks he'll obtain their friendship (and, perhaps, some of their power) if he parrots their racist screeds against other people of color--which, face it, is exactly what nonchalantly describing wiping out much of the Middle East with nuclear weapons is. Uncle Tom is too kind a description for someone advocating--or, at the very least, dismissing the moral implications inherent in--nuclear war against countries, full of brown people, which have not attacked us, and do not have the ability to attack us with such weapons. (Williams writes with certainty of "Iran's... nuclear weapons program" and yet, there is no definitive evidence to date that they have a nuclear weapons program. Nuking millions on the basis of unproven assertions and misapprehension of threats on the part of the far right hardly qualifies as a morally justified act in any rational person's book.)

What a fuckin' putz. What he's saying here is that it's really okay to kill millions of people with nuclear weapons because the people in power in this country may want them killed--as an expression of sheer will and expediency. (Though he says, "I'm sure there are other less drastic military options," the inference to be drawn throughout is that the only reason we haven't already done so is because "today's Americans" are afraid and weak.)

Backhandedly, he wishes to validate the view that the winners are never tried for war crimes. If Williams had given even a moment's thought about Dresden and Tokyo and Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he would have remembered Curtis LeMay's words: "I suppose if we'd lost the war, we would have been tried as war criminals." Instead, he says: "Such an argument would have fallen on deaf ears during World War II when we firebombed cities in Germany and Japan. The loss of lives through saturation bombing far exceeded those lost through the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki." This is his way of saying that it would be okay to kill innocent people with atomic weapons. We've done worse, after all, he intimates, in an equally good cause (precisely the sophistry necessary to conflate WWII with terrorism today). Ol' Walt may find fine moral distinctions between exterminating millions of innocents with atomic weapons instead of mass incendiary bomb attacks, but, alas, I do not. Neither do those who lived through such attacks.

Implicit in Williams' argument is that we can engage in war crimes if we assert, with some firmness, that we are right, and that, if we bury central Asia in nuclear explosions, we'll win and we won't be war criminals, because we were not weak and won. Does ol' Walt pretend to the same logic as Gen. LeMay? It seems so.

Okay, let's say that Williams is right and terrorism disappears (for a few years) after we expend a few hundred nukes on Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, North Korea and China. Let's say, for argument's sake, that we obliterate the people inhabiting a third of the world in doing so. Who are the war criminals? The millions of innocents who did nothing overt to us... or us, who killed millions because the right-wing crazies in our society (along with good, dependable, loyal Walt) thought that striking in speculative, preventive fashion with massive nuclear force was the same thing as being morally correct? Does that somehow change the nature of a war crime of incalculable proportions? It does not.

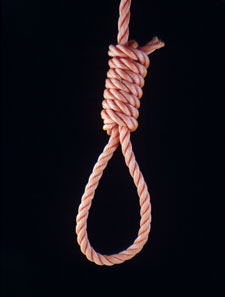

One would think (wrongly, apparently, in Dr. Williams' case) that a black man in America would understand that there's no difference between a lynching noose and a nuke, except for scale, and that the higher moral ground depends not at all upon who's on which end of the rope.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home