Sinners in the Hands of an Angry Chance....

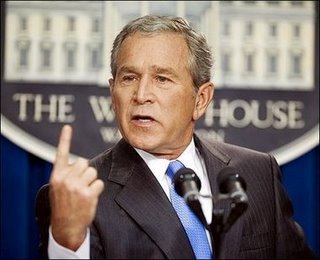

Bush has finally shown himself to be the literal descendent of Jerzy Kosinski's Chance, the Gardener, reducing every press opportunity and speech to a laundry list of stock phrases absent of contextual reality and repeated abstractions never meant to be elucidated upon. In answering questions yesterday, Bush resorted to "prevail" eleven times, and between Blair and Bush (a routine that's more and more beginning to seem, unintentionally, like the comedic pairing of Spike Milligan and Tommy Smothers), the two used the word "important" forty-six times in about an hour. When the tone of reporters' questions began to verge on exasperated, the linguistically-desiccated Bush turned testy, truculent and dismissive (so,

Bush has finally shown himself to be the literal descendent of Jerzy Kosinski's Chance, the Gardener, reducing every press opportunity and speech to a laundry list of stock phrases absent of contextual reality and repeated abstractions never meant to be elucidated upon. In answering questions yesterday, Bush resorted to "prevail" eleven times, and between Blair and Bush (a routine that's more and more beginning to seem, unintentionally, like the comedic pairing of Spike Milligan and Tommy Smothers), the two used the word "important" forty-six times in about an hour. When the tone of reporters' questions began to verge on exasperated, the linguistically-desiccated Bush turned testy, truculent and dismissive (so,what's new?).

Orwell would be laughing his ass off. After yesterday, I can imagine him hearing such a speech, wadding up a draft copy of "Politics and the English Language" and throwing it over his shoulder with a helpless shrug. What he would likely find funniest about it, though, is the way the press in the United States takes such mindless drivel seriously, adding thousands of tons of paper and ink to Bush's words to give them weight they do not innately possess, lest they drift off aimlessly, mimicking the thought processes which produced them.

H.L. Mencken knew how to deal with mental lightweights like Bush (he had his own example on which to gain much practice, Warren Gamaliel Harding). Mencken treated Harding as he should have been treated--as a idiotic bumbler, a buffoon and a serial practitioner of verbal self-immolation. Harding, though, was mostly harmless. Bush, however, is like a petulant teenager with a sense of extreme entitlement who keeps trying to burn down his parents' house because he doesn't get what he wants and his parents won't do as he says.

That ought to encourage the press and the pundits to adopt language even more acidic than that applied to Harding by Mencken, but they do not. Part of the reason for that, of course, is that Karl Rove (Bush's inner juvenile delinquent) has made it clear to the press that even the suggestion of mild skepticism toward Bush or his "ideas" will be dealt with harshly. The other part of the reason is that the press treats such threats as real and behaves accordingly, for reasons of its own that will be debated for decades to come--because, to a corporate press, access to power is more important than speaking truth to it.

Despite this, the public is still getting a sense of just how seriously they were duped by both Bush and the press, and is experiencing more than just a sense of buyer's regret. Favorability ratings of Bush are approaching the lows experienced by Nixon and Bush's father. Sentiment both for the war itself and Bush's prosecution of it are flagging badly. Despite the pundits in the press cheerfully repeating in 2000 the news that "the adults are back in charge," the public is now rapidly coming to the opinion that what the press once called "plain speaking" was and is just the confused, self-important rantings of an adolescent idiot, signifying nothing resembling a national policy.

In idle moments, I often wonder what Mencken would have said of Bush. He likely would have been capable of seeing through the photo-ops and the faux toe-in-the-dirt, "aw, shucks" routine of the campaigning Bush, and skewered him as the patrician Connecticut Yankee carpetbagging in the South, just like his father before him. He would have seen him, with genuine perception, as the wastrel son whose life was the inevitable culmination of the combination of perceived aristocratic entitlement, social inbreeding and the general bad manners of the indolent rich. He would likely have noted that not only is Bush an emperor without clothes, but is, as well, a pretender to the emperor's throne, with a $500 cowboy hat for a crown and a $3000 mountain bike for a sceptre.

He undoubtedly would have noted Bush's tendency to talk in circles, and made short shrift of Bush's fulsome employment of as little as possible of his six-hundred-word vocabulary in every irritatingly deceptive extemporaneous speech. No doubt, too, from the paucity of Bush's speech, he inevitably would have been led to the most direct and obvious of conclusions about Bush's mental state and capacity, something upon which current members of the press are simply too fearful to speculate, as they are likely fretful about being charged with inciting to riot. When Bush began to talk of God acting through him, Mencken would have had an opportunity he rarely had in his own lifetime, the chance to finely dissect the defects of both religion and politicians without having to alternate between examples.

Of all this I am reasonably certain, if only because Mencken delineated Bush long before Bush was born. For example: "Firmness in decision is often merely a form of stupidity. It indicates an inability to think the same thing out twice."

Kosinski's Being There was a farcical commentary on the utter credulousness of the American press and public, which Mencken, were he alive today and observing Bush in his current habitat, would have found entirely justified. Orwell would have shrugged and said, "it's not polite to rub your noses in it, but I told you so." While Kosinski was a strange, in ways unfathomable person, he still let us know something about ourselves which we dutifully and promptly ignored. Mencken, who was skeptical and iconoclastic about almost everything and was likely wrong about a great many things, nevertheless could pin down the identity and ill intentions of politicians such as Bush as if they were objects for entomological display. Orwell saw, in 1948, that political speech had become so corrupted and absent of meaning that it would inevitably lead to "free-fire zones," "collateral damage" and, sooner than later, to the passive-aggressive grunts of a psychically malformed, willfully ignorant petty tyrant made President.

We were duly and properly warned of what we now continue to endure....

1 Comments:

Dear Comrade,

Please visit http://ministryoflove.wordpress.com to learn about our Orwellian protest of the Military Commissions Act.

Regards,

O'Brien

By Anonymous, at 1:49 PM

Anonymous, at 1:49 PM

Post a Comment

<< Home